Indian Penal Code Ppt

Posted By admin On 26/05/19| The Indian Penal Code, 1860 | |

|---|---|

| An Act to provide a general penal code in India | |

| Citation | Act No. 45 of 1860 |

| Territorial extent | India (except the state of Jammu and Kashmir) |

| Enacted by | Imperial Legislative Council |

| Date enacted | 6 October 1860 |

| Date assented to | 6 October 1860 |

| Date commenced | 1 January 1862 |

| Committee report | First Law Commission |

| Amends | |

| seeAmendments | |

| Related legislation | |

| Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 | |

| Status: Amended | |

IPC Chapter XVII - Offences Against Property from the Indian Penal Code of 1860, a mobile friendly and searchable Bare Act, by Advocate Raman Devgan, Chandigarh. Download Presentation INDIAN PENAL CODE An Image/Link below is provided (as is) to download presentation. Download Policy: Content on the Website is provided to you AS IS for your information and personal use and may not be sold / licensed / shared on other. You can also find Introduction to Indian Penal Code (IPC) - Criminal Law ppt and other CLAT slides as well. If you want Introduction to Indian Penal Code (IPC) - Criminal Law notes & Videos, you can search for the same too.

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) is the official criminal code of India. It is a comprehensive code intended to cover all substantive aspects of criminal law. The code was drafted in 1860 on the recommendations of first law commission of India established in 1834 under the Charter Act of 1833 under the Chairmanship of LordThomas Babington Macaulay.[1][2][3] It came into force in British India during the early British Raj period in 1862. However, it did not apply automatically in the Princely states, which had their own courts and legal systems until the 1940s. The Code has since been amended several times and is now supplemented by other criminal provisions.

After the partition of the British Indian Empire, the Indian Penal Code was inherited by its successor states, the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan, where it continues independently as the Pakistan Penal Code. The Ranbir Penal Code (R.P.C) applicable in Jammu and Kashmir is also based on this Code.[2] After the separation of Bangladesh (former East Pakistan) from Pakistan, the code continued in force there. The Code was also adopted by the British colonial authorities in Colonial Burma, Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), the Straits Settlements (now part of Malaysia), Singapore and Brunei, and remains the basis of the criminal codes in those countries.

- 4Controversies

History[edit]

The draft of the Indian Penal Code was prepared by the First Law Commission, chaired by Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1834 and was submitted to Governor-General of India Council in 1835. Its basis is the law of England freed from superfluities, technicalities and local peculiarities. Elements were also derived from the Napoleonic Code and from Edward Livingston's Louisiana Civil Code of 1825. The first final draft of the Indian Penal Code was submitted to the Governor-General of India in Council in 1837, but the draft was again revised. The drafting was completed in 1850 and the Code was presented to the Legislative Council in 1856, but it did not take its place on the statute book of British India until a generation later, following the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The draft then underwent a very careful revision at the hands of Barnes Peacock, who later became the first Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court, and the future puisne judges of the Calcutta High Court, who were members of the Legislative Council, and was passed into law on 6 October 1860.[4] The Code came into operation on 1 January 1862. Macaulay did not survive to see his masterpiece come into force, having died near the end of 1859.

Objective[edit]

The objective of this Act is to provide a general penal code for India.[5] Though not the initial objective, the Act does not repeal the penal laws which were in force at the time of coming into force in India. This was so because the Code does not contain all the offences and it was possible that some offences might have still been left out of the Code, which were not intended to be exempted from penal consequences. Though this Code consolidates the whole of the law on the subject and is exhaustive on the matters in respect of which it declares the law,many more penal statutes governing various offences have been created in addition to the code.

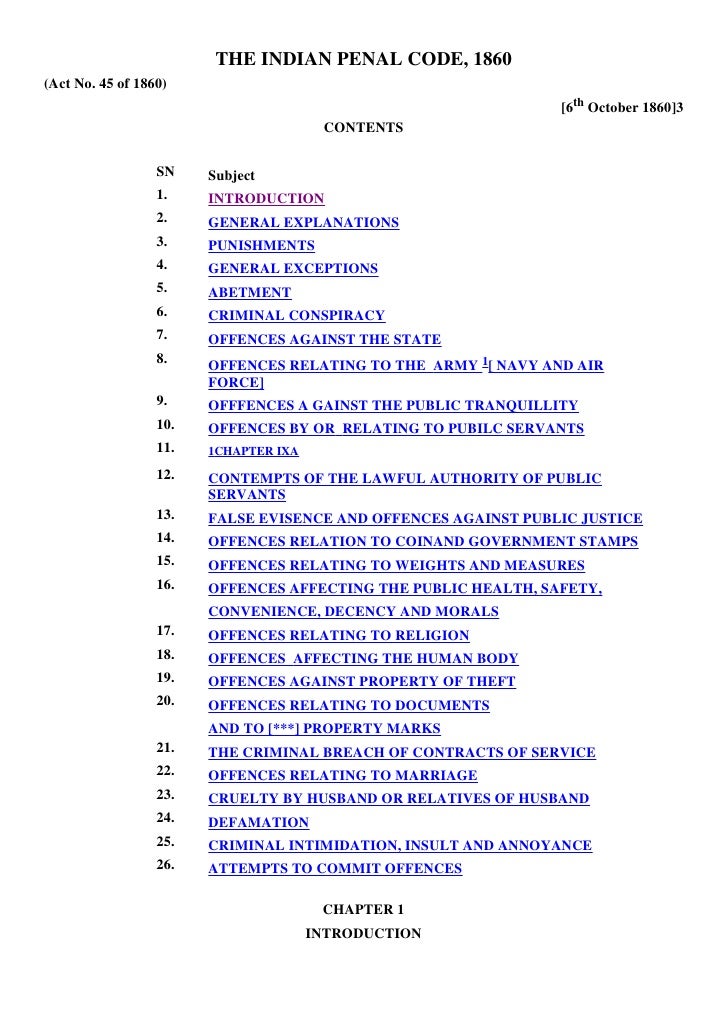

Structure[edit]

The Indian Penal Code of 1860, sub-divided into 23 chapters, comprises 511 sections. The Code starts with an introduction, provides explanations and exceptions used in it, and covers a wide range of offences. The Outline is presented in the following table:[6]

| Chapter | Sections covered | Classification of offences |

|---|---|---|

| Chapter I | Sections 1 to 5 | Introduction |

| Chapter II | Sections 6 to 52 | General Explanations |

| Chapter III | Sections 53 to 75 | of Punishments |

| Chapter IV | Sections 76 to 106 | General Exceptions of the Right of Private Defence (Sections 96 to 106) |

| Chapter V | Sections 107 to 120 | Of Abetment |

| Chapter VA | Sections 120A to 120B | Criminal Conspiracy |

| Chapter VI | Sections 121 to 130 | Of Offences against the State |

| Chapter VII | Sections 131 to 140 | Of Offences relating to the Army, Navy and Air Force |

| Chapter VIII | Sections 141 to 160 | Of Offences against the Public Tranquillity |

| Chapter IX | Sections 161 to 171 | Of Offences by or relating to Public Servants |

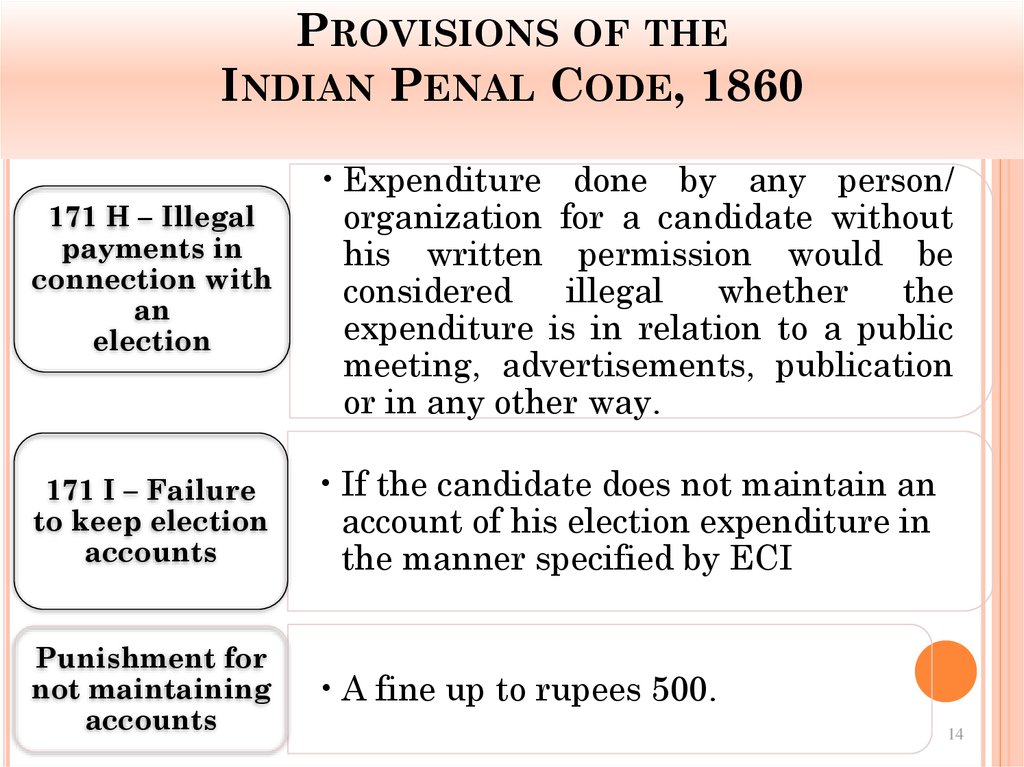

| Chapter IXA | Sections 171A to 171I | Of Offences Relating to Elections |

| Chapter X | Sections 172 to 190 | Of Contempts of Lawful Authority of Public Servants |

| Chapter XI | Sections 191 to 229 | Of False Evidence and Offences against Public Justice |

| Chapter XII | Sections 230 to 263 | Of Offences relating to coin and Government Stamps |

| Chapter XIII | Sections 264 to 267 | Of Offences relating to Weight and Measures |

| Chapter XIV | Sections 268 to 294 | Of Offences affecting the Public Health, Safety, Convenience, Decency and Morals. |

| Chapter XV | Sections 295 to 298 | Of Offences relating to Religion |

| Chapter XVI | Sections 299 to 377 | Of Offences affecting the Human Body.

|

| Chapter XVII | Sections 378 to 462 | Of Offences Against Property

|

| Chapter XVIII | Section 463 to 489 -E | Offences relating to Documents and Property Marks

|

| Chapter XIX | Sections 490 to 492 | Of the Criminal Breach of Contracts of Service |

| Chapter XX | Sections 493 to 498 | Of Offences Relating to Marriage |

| Chapter XXA | Sections 498A | Of Cruelty by Husband or Relatives of Husband |

| Chapter XXI | Sections 499 to 502 | Of Defamation |

| Chapter XXII | Sections 503 to 510 | Of Criminal intimidation, Insult and Annoyance |

| Chapter XXIII | Section 511 | Of Attempts to Commit Offences |

Controversies[edit]

Various sections of the Indian Penal Code are controversial. They are challenged in courts claiming as against constitution of India. Also there is demand for abolition of some controversial IPC sections completely or partially.

Unnatural Offences (Sodomy) - Section 377[edit]

Whoever, voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment of life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.

Explanation - Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section.[7]

- Section 377 The Delhi High Court on 2 July 2009 gave a liberal interpretation to this section and laid down that this section can not be used to punish an act of consensual sexual intercourse between two same sex individuals.[8]

- On 11 December 2013, Supreme Court of India over-ruled the judgment given by Delhi High court in 2009 and clarified that 'Section 377, which holds same-sex relations unnatural, does not suffer from unconstitutionality'. The Bench said: 'We hold that Section 377 does not suffer from .. unconstitutionality and the declaration made by the Division Bench of the High Court is legally unsustainable.' It, however, said: 'Notwithstanding this verdict, the competent legislature shall be free to consider the desirability and propriety of deleting Section 377 from the statute book or amend it as per the suggestion made by Attorney-General G.E. Vahanvati.'[9]

- On 8 January 2018, the Supreme Court agreed to reconsider its 2013 decision and after much deliberation agreed to decriminalise the parts of Section 377 that criminalised same sex relations on 6 September 2018. [10] The judgement of Suresh Kaushal v. Naz Foundation is overruled.[11]

Attempt to Commit Suicide - Section 309[edit]

The Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code deals with an unsuccessful attempt to suicide. Attempting to commit suicide and doing any act towards the commission of the offence is punishable with imprisonment up to one year or with fine or with both. Considering long-standing demand and recommendations of the Law Commission of India, which has repeatedly endorsed the repeal of this section, the Government of India in December 2014 decided to decriminalise attempt to commit suicide by dropping Section 309 of IPC from the statute book. Though this decision found favour with most of the states, a few others argued that it would make law enforcement agencies helpless against people who resort to fast unto death, self-immolation, etc., pointing out the case of anti-AFSPA activist Irom Chanu Sharmila.[12] In February 2015, the Legislative Department of the Ministry of Law and Justice was asked by the Government to prepare a draft Amendment Bill in this regard.[13]

In an August 2015 ruling, the Rajasthan High Court made the Jain practice of undertaking voluntary death by fasting at the end of a person's life, known as Santhara, punishable under sections 306 and 309 of the IPC. This led to some controversy, with some sections of the Jain community urging the Prime Minister to move the Supreme Court against the order.[14][15]On 31 August 2015, the Supreme Court admitted the petition by Akhil Bharat Varshiya Digambar Jain Parishad and granted leave. It stayed the decision of the High Court and lifted the ban on the practice.

Adultery - Section 497[edit]

The Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code has been criticised on the one hand for allegedly treating woman as the private property of her husband, and on the other hand for giving women complete protection against punishment for adultery.[16][17] This section was unanimously struck down on 27th September 2018 by a five judge bench of the Supreme Court in case of Joseph Shine v. Union of India as being unconstitutional and demeaning to the dignity of women. Adultery continues to be a ground for seeking divorce in a Civil Court, but is no longer a criminal offence in India.

Death penalty (Capital Punishment)[edit]

Sections 120B (criminal conspiracy), 121 (war against the Government of India), 132 (mutiny), 194 (false evidence to procure conviction for a capital offence), 302, 303 (murder), 305 (abetting suicide), 364A (kidnapping for ransom), 364A (banditry with murder), 376A (rape) have death penalty as punishment. There is ongoing debate for abolishing capital punishment.[18]

Criminal justice reforms[edit]

In 2003, the Malimath Committee submitted its report recommending several far-reaching penal reforms including separation of investigation and prosecution (similar to the CPS in the UK) to streamline criminal justice system.[19] The essence of the report was a perceived need for shift from an adversarial to an inquisitorial criminal justice system, based on the Continental European systems.

Virtua Tennis 4. Release Date: 2011. Reqs.: Very low (6/14). Popularity: ~950# □. Reviews: Positive (8.4). Genre: Sports. Developer: SEGA. Virtua tennis 4 pc. PETITION: BRING BACK-VIRTUA TENNIS 4-TO STEAM STORE!!! I would like to. PC Virtua Tennis 4 online ARGENTINA vs USA. Chalito View videos. Amazon.com: Virtua Tennis 4: Software. Download Alexa for your Windows 10 PC for free. Experience the convenience of Alexa, now on your PC. Download Virtua Tennis 4 [Download] and play today. No Description Provided System. Download Alexa for your Windows 10 PC for free. Experience the.

Amendments[edit]

The Code has been amended several times.[20][21]

| S. No. | Short title of amending legislation | No. | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Repealing Act, 1870 | 14 | 1870 |

| 2 | The Indian Penal Code Amendment Act, 1870 | 27 | 1870 |

| 3 | The Indian Penal Code Amendment Act, 1872 | 19 | 1872 |

| 4 | The Indian Oaths Act, 1873 | 10 | 1873 |

| 5 | The Indian Penal Code Amendment Act, 1882 | 8 | 1882 |

| 6 | The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1882 | 10 | 1882 |

| 7 | The Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1886 | 10 | 1886 |

| 8 | The Indian Marine Act, 1887 | 14 | 1887 |

| 9 | The Metal Tokens Act, 1889 | 1 | 1889 |

| 10 | The Indian Merchandise Marks Act, 1889 | 4 | 1889 |

| 11 | The Cantonments Act, 1889 | 13 | 1889 |

| 12 | The Indian Railways Act, 1890 | 9 | 1890 |

| 13 | The Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1891 | 10 | 1891 |

| 14 | The Amending Act, 1891 | 12 | 1891 |

| 15 | The Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1894 | 3 | 1894 |

| 16 | The Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1895 | 3 | 1895 |

| 17 | The Indian Penal Code Amendment Act, 1896 | 6 | 1896 |

| 18 | The Indian Penal Code Amendment Act, 1898 | 4 | 1898 |

| 19 | The Currency-Notes Forgery Act, 1899 | 12 | 1899 |

| 20 | The Indian Penal Code Amendment Act, 1910 | 3 | 1910 |

| 21 | The Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1913 | 8 | 1913 |

| 22 | The Indian Elections Offences and Inquiries Act, 1920 | 39 | 1920 |

| 23 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1921 | 16 | 1921 |

| 24 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1923 | 20 | 1923 |

| 25 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1924 | 5 | 1924 |

| 26 | The Indian Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1924 | 18 | 1924 |

| 27 | The Workmen's Breach of Contract (Repealing) Act, 1925 | 3 | 1925 |

| 29 | The Obscene Publications Act, 1925 | 8 | 1925 |

| 29 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1925 | 29 | 1925 |

| 30 | The Repealing and Amending Act, 1927 | 10 | 1927 |

| 31 | The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1927 | 25 | 1927 |

| 32 | The Repealing and Amending Act, 1930 | 8 | 1930 |

| 33 | The Indian Air Force Act, 1932 | 14 | 1932 |

| 34 | The Amending Act, 1934 | 35 | 1934 |

| 35 | The Government of India (Adaptation of Indian Laws) Order, 1937 | N/A | 1937 |

| 36 | The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1939 | 22 | 1939 |

| 37 | The Offences on Ships and Aircraft Act, 1940 | 4 | 1940 |

| 38 | The Indian Merchandise Marks (Amendment) Act, 1941 | 2 | 1941 |

| 39 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1942 | 8 | 1942 |

| 40 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1943 | 6 | 1943 |

| 41 | The Indian Independence (Adaptation of Central Acts and Ordinances) Order, 1948 | N/A | 1948 |

| 42 | The Criminal Law (Removal of Racial Discriminations) Act, 1949 | 17 | 1949 |

| 43 | The Indian Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 1949 | 42 | 1949 |

| 44 | The Adaptation of Laws Order, 1950 | N/A | 1950 |

| 45 | The Repealing and Amending Act, 1950 | 35 | 1950 |

| 46 | The Part B States (Laws) Act, 1951 | 3 | 1951 |

| 47 | The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1952 | 46 | 1952 |

| 48 | The Repealing and Amending Act, 1952 | 48 | 1952 |

| 49 | The Repealing and Amending Act, 1953 | 42 | 1953 |

| 50 | The Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 1955 | 26 | 1955 |

| 51 | The Adaptation of Laws (No.2) Order, 1956 | N/A | 1956 |

| 52 | The Repealing and Amending Act, 1957 | 36 | 1957 |

| 53 | The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1958 | 2 | 1958 |

| 54 | The Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958 | 43 | 1958 |

| 55 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1959 | 52 | 1959 |

| 56 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1961 | 41 | 1961 |

| 57 | The Anti-Corruption Laws (Amendment) Act, 1964 | 40 | 1964 |

| 58 | The Criminal and Election Laws Amendment Act, 1969 | 35 | 1969 |

| 59 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1969 | 36 | 1969 |

| 60 | The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 1972 | 31 | 1972 |

| 61 | The Employees' Provident Funds and Family Pension Fund (Amendment) Act, 1973 | 40 | 1973 |

| 62 | The Employees' State Insurance (Amendment) Act, 1975 | 38 | 1975 |

| 63 | The Election Laws (Amendment) Act, 1975 | 40 | 1975 |

| 64 | The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 1983 | 43 | 1983 |

| 65 | The Criminal Law (Second Amendment) Act, 1983 | 46 | 1983 |

| 66 | The Dowry Prohibition (Amendment) Act, 1986 | 43 | 1986 |

| 67 | The Employees' Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 1988 | 33 | 1988 |

| 68 | The Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 | 49 | 1988 |

| 69 | The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 1993 | 42 | 1993 |

| 70 | The Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Act, 1995 | 24 | 1995 |

| 71 | The Information Technology Act, 2000 | 21 | 2000 |

| 72 | The Election Laws (Amendment) Act, 2003 | 24 | 2003 |

| 73 | The Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2005 | 25 | 2005 |

| 74 | The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2005 | 2 | 2006 |

| 75 | The Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008 | 10 | 2009 |

| 76 | The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 | 13 | 2013 |

| 77 | The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2018 | 2018 |

Acclaim[edit]

The Code is universally acknowledged as a cogently drafted code, ahead of its time. It has substantially survived for over 150 years in several jurisdictions without major amendments. Nicholas Phillips, Justice of Supreme Court of United Kingdom applauded the efficacy and relevance of IPC while commemorating 150 years of IPC.[22] Modern crimes involving technology unheard of during Macaulay's time fit easily within the Code[citation needed] mainly because of the broadness of the Code's drafting.

Cultural references[edit]

Some references to specific sections (called dafa'a in Hindi-Urdu, دفعہ or दफ़आ/दफ़ा) of the IPC have entered popular speech in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. For instance, con men are referred to as 420s (chaar-sau-bees in Hindi-Urdu) after Section 420 which covers cheating.[23] Similarly, specific reference to section 302 ('tazīrāt-e-Hind dafā tīn-sau-do ke tehet sazā-e-maut', 'punishment of death under section 302 of the Indian Penal Code'), which covers the death penalty, have become part of common knowledge in the region due to repeated mentions of it in Bollywood movies and regional pulp literature.[24][25]Dafa 302 was also the name of a Bollywood movie released in 1975.[26] Similarly, Shree 420 was the name of a 1955 Bollywood movie starring Raj Kapoor.[27] and Chachi 420 was a Bollywood movie released in 1997 starring Kamal Haasan.[28]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Universal's Guide to Judicial Service Examination. Universal Law Publishing. p. 2. ISBN978-93-5035-029-4.

- ^ abLal Kalla, Krishan (1985). The Literary Heritage of Kashmir. Jammu and Kashmir: Mittal Publications. p. 75. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^'Law Commission of India - Early Beginnings'. Law Commission of India. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^'Historical Introduction to IPC (PDF)'(PDF).

- ^'Preamble of IPC (download IPC in PDF)'.

- ^B.M.Gandhi. Indian Panel Code (2013 ed.). EBC. pp. 1–832. ISBN978-81-7012-892-2.

- ^B.M.Gandhi. Indian Penal Code. EBC. pp. 1–796. ISBN978-81-7012-892-2.

- ^'Delhi High Court strikes down Section 377 of IPC'. The Hindu. 3 July 2009. ISSN0971-751X. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^Venkatesan, J. (11 December 2013). 'Supreme Court sets aside Delhi HC verdict decriminalising gay sex'. The Hindu. ISSN0971-751X. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^'SC decriminalises Section 377: A timeline of the case'. Times of India. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^'Supreme Court's decision on Section 377: Separate decision of 5 Judges [Read Judgement]'. www.lawji.in. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^'Government decriminalizes attempt to commit suicide, removes section 309'. The Times of India. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^'Attempt to Suicide'. Press Information Bureau. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^'Rajasthan HC says Santhara illegal, Jain saints want PM Modi to move SC'. The Indian Express. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^'Rajasthan HC bans starvation ritual 'Santhara', says fasting unto death not essential tenet of Jainism'. IBN Live. CNN-IBN. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^'Wife is private property, so no trespassing'. The Times of india. 17 July 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^'Adultery law biased against men, says Supreme Court'. The Times of India. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^Abrams, Corinne (3 September 2015). 'The Reasons India's Law Commission Says the Death Penalty Should Be Scrapped'.

- ^'IPC Reform Committee recommends separation of investigation from prosecution powers (pdf)'(PDF). Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^Parliament of India. 'The Indian Penal Code'(PDF). childlineindia.org.in. Retrieved 7 June 2015.This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^The Indian Penal Code, 1860. Current Publications. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^'IPC's endurance lauded'. The New Indian Express. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^Henry Scholberg (1992), The return of the Raj: a novel, NorthStar Publications, 1992,

.. People were saying, 'Twenty plus Four equals Char Sau Bees.' Char Sou Bees is 420 which is the number of the law that has to do with counterfeiting ..

- ^Star Plus, The Great Indian Laughter Challenge – Jokes Book, Popular Prakashan, ISBN978-81-7991-343-7,

.. Tazeerat-e-hind, dafa 302 ke tahat, mujrim ko maut ki saza sunai jaati hai ..

- ^Alok Tomar; Monisha Shah; Jonathan Lynn (2001), Ji Mantriji: The diaries of Shri Suryaprakash Singh, Penguin Books in association with BBC Worldwide, 2001, ISBN978-0-14-302767-6,

.. we'd have the death penalty back tomorrow. Dafa 302, taaziraat-e-Hind .. to be hung by the neck until death ..

- ^D. P. Mishra (1 September 2006), Great masters of Indian cinema: the Dadasaheb Phalke Award winnersGreat Masters of Indian Cinema Series, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 2006, ISBN978-81-230-1361-9,

.. Badti Ka Naam Dadhi ( 1975), Chhoti Si Baat ( 1975), Dafa 302 ( 1 975), Chori Mera Kaam ( 1975), Ek Mahal Ho Sapnon Ka (1975) ..

- ^'Shree 420' – via www.imdb.com.

- ^Haasan, Kamal; Puri, Amrish; Puri, Om; Tabu (19 December 1997), Chachi 420, retrieved 3 April 2017

Further reading[edit]

- C.K.Takwani (2014). Indian Penal Code. Eastern Book Company.

- Murlidhar Chaturvedi (2011). Bhartiya Dand Sanhita,1860. EBC. ISBN978-93-5028-140-6.

- Surender Malik; Sudeep Malik (2015). Supreme Court on Penal Code. EBC. ISBN978-93-5145-218-8.

Indian Penal Code Ppt Download

External links[edit]

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code is a section of the Indian Penal Code introduced in 1864 during the British rule of India. Modelled on the Buggery Act of 1533, it makes sexual activities 'against the order of nature' illegal. On 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India ruled that the application of Section 377 to consensual homosexual sex between adults was unconstitutional, 'irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary',[1] but that Section 377 remains in force relating to sex with minors, non-consensual sexual acts, and bestiality.[2]

Portions of the section were first struck down as unconstitutional with respect to gay sex by the Delhi High Court in July 2009.[3][4][5] That judgement was overturned by the Supreme Court of India (SC) on 11 December 2013 in Suresh Kumar Koushal vs. Naz Foundation. The Court held that amending or repealing section 377 should be a matter left to Parliament, not the judiciary.[6][7] On 6 February 2016, a three-member bench of the Court reviewed curative petitions submitted by the Naz Foundation and others, and decided that they would be reviewed by a five-member constitutional bench.[8]

On 24 August 2017, the Supreme Court upheld the right to privacy as a fundamental right under the Constitution in the landmark Puttuswamy judgement. The Court also called for equality and condemned discrimination, stated that the protection of sexual orientation lies at the core of the fundamental rights and that the rights of the LGBT population are real and founded on constitutional doctrine.[9] This judgement was believed to imply the unconstitutionality of section 377.[10][11][12]

In January 2018, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a petition to revisit the 2013 Naz Foundation judgment. On 6 September 2018, the Court ruled unanimously in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India that Section 377 was unconstitutional 'in so far as it criminalises consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex'.[13][14]

- 2Public perception

- 3Views of political parties

- 5Judiciary action

Text[edit]

377. Unnatural offences: Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.

Explanation: Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section.[15][16]

Public perception[edit]

Support[edit]

In 2008 Additional Solicitor General PP Malhotra said: 'Homosexuality is a social vice and the state has the power to contain it. [Decriminalising homosexuality] may create [a] breach of peace. If it is allowed then [the] evil of AIDS and HIV would further spread and harm the people. It would lead to a big health hazard and degrade moral values of society.' This view was shared by the Home Ministry.[17]

11 December 2013 judgement of the Supreme Court, upholding Section 377 was met with support from religious leaders. The Daily News and Analysis called it 'the univocal unity of religious leaders in expressing their homophobic attitude. Usually divisive and almost always seen tearing down each other’s religious beliefs, leaders across sections came forward in decrying homosexuality and expressing their solidarity with the judgement.'[18] The Daily News and Analysis article added that Baba Ramdev, India's well-known yoga guru, after praying that journalists not 'turn homosexual', stated he could 'cure' homosexuality through yoga and called it 'a bad addiction'. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad's vice-president Om Prakash Singhal said, 'This is a right decision, we welcome it. Homosexuality is against Indian culture, against nature and against science. We are regressing, going back to when we were almost like animals. The SC had protected our culture.' The article states that Singhal further went to dismiss HIV/AIDS concerns within the LGBT community as, 'It is understood that when you try to suppress one anomaly, there will be a break-out of a few more.' (Traditionally, Indian culture, or at least Hinduism, has been more ambivalent about homosexuality than Singhal suggests.)Maulana Madni of the Jamiat Ulema echoes this in the article, stating that 'Homosexuality is a crime according to scriptures and is unnatural. People cannot consider themselves to be exclusive of a society.. In a society, a family is made up of a man and a woman, not a woman and a woman, or a man and a man.' Rabbi Ezekiel Issac Malekar, honorary secretary of the Judah Hyam Synagogue, in upholding the judgment was also quoted as saying 'In Judaism, our scriptures do not permit homosexuality.' Reverend Paul Swarup of the Cathedral Church of the Redemption in Delhi in stating his views on what he believes to be the unnaturalness of homosexuality, stated 'Spiritually, human sexual relations are identified as those shared by a man and a woman. The Supreme Court’s view is an endorsement of our scriptures.'

Opposition and criticism[edit]

Indian Penal Code 1860

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare opposed the upholding of Section 377, stating that it would hinder anti-HIV/AIDS efforts[19][20]. According to the NCRB, in 2015, 1,491 people were arrested under Section 377, including 207 minors (14%) and 16 women.[21]Human Rights Watch also argues that the law has been used to harass HIV/AIDS prevention efforts, as well as sex workers, homosexuals, and other groups at risk of the disease,[22] even though those found guilty of extortion in relation to accusations that relate to Section 377 may face a life sentence under a special provision of Section 389 of the IPC.[23] The People's Union for Civil Liberties has published two reports of the rights violations faced by sexual minorities[24] and, in particular, transsexuals in India.[25]

In 2006 it came under criticism from 100 Indian literary figures,[26] most prominently Vikram Seth. The law subsequently came in for criticism from several ministers, most prominently Anbumani Ramadoss[27] and Oscar Fernandes.[28] In 2008, a judge of the Bombay High Court also called for the scrapping of the law.[29]

The United Nations said that the ban violates international law. United Nations human rights chief Navi Pillay stated that 'Criminalising private, consensual same-sex sexual conduct violates the rights to privacy and to non-discrimination enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which India has ratified', and that the decision 'represents a significant step backwards for India and a blow for human rights.', voicing hope that the Court might exercise its review procedure.[30]

Views of political parties[edit]

Support[edit]

Rajnath Singh, a member of the ruling party BJP and the Home Minister, is on record shortly after the law was re-instated in 2013, claiming that his party is 'unambiguously' in favour of the law, also claiming that 'We will state (at an all-party meeting if it is called) that we support Section 377 because we believe that homosexuality is an unnatural act and cannot be supported.”[31]Yogi Adityanath, BJP MP, Chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, endorsed Radev's comments, saying he welcomes the verdict and will 'oppose any move to decriminalise homosexuality.'[32]

The Samajwadi Party made it clear that it will oppose any amendments to the section if it comes in Parliament for discussion, calling homosexuality 'unethical and immoral.'[33]Ram Gopal Yadav stated that they support the Supreme Court decision as 'It is completely against the culture of our nation.'[32]

The Congress party led UPA government also supported the law during the initial Naz Foundation case, stating that gay sex was 'immoral' and that it cannot be decriminalised.[34]

Bharatiya Janata Party leader Dr Subramanian Swamy said that homosexuality was not a normal thing and, in fact, against Hindutva. Swamy’s comment came ahead of the Supreme Court’s hearing of petitions against Section 377, The BJP leader went on to say that the government should invest in medical research to see if homosexuality can be cured. “It is not a normal thing. We cannot celebrate it, it's a danger to our national security' 'There is a lot of money behind it. The Americans want to open gay bars, and it'll be a cover for pedophiles and a huge rise in HIV cases.' he said.[35]

Opposition[edit]

Finance Minister and BJP member Arun Jaitley has a different view from Rajnath Singh, saying that 'Supreme Court should not have reversed the Delhi High Court order which de-criminalised consensual sex between gay adults' and 'When millions of people the world over are having alternative sexual preferences, it is too late in the day to propound the view that they should be jailed.'.[36][37] BJP spokesperson Shaina NC said her party supports decriminalisation of homosexuality. 'We are for decriminalising homosexuality. That is the progressive way forward.'[38]

In December 2013, Indian National Congress vice-president Rahul Gandhi came out in support of LGBT rights and said that 'every individual had the right to choose'. He also said 'These are personal choices. This country is known for its freedom, freedom of expression. So let that be. I hope that Parliament will address the issue and uphold the constitutional guarantee of life and liberty to all citizens of India, including those directly affected by the judgement', he said. The LGBT rights movement in India was also part of the election manifesto of the Congress for the 2014 general elections.[36] Senior Congress leader and former Finance Minister P Chidambaram expressed his disappointment, saying we have gone back in time and must quickly reverse the judgement.[32] He also said that 'Section 377, in my view, was rightly struck down or read down by the Delhi High Court judgement by Justice AP Shah.'[39]

The RSS revised its position, the leader Dattatreya Hosabale reportedly saying, 'no criminalisation, but no glorification either.'[40]

After the 2013 verdict, the Aam Aadmi Party put on their website:

The Aam Aadmi party is disappointed with the judgment of the Supreme Court upholding the Section 377 of the IPC and reversing the landmark judgment of the Delhi High Court on the subject. The Supreme Court judgment thus criminalises the personal behaviour of consenting adults. All those who are born with or choose a different sexual orientation would thus be placed at the mercy of the police. This not only violates the human rights of such individuals, but goes against the liberal values of our Constitution, and the spirit of our times. Aam Aadmi Party hopes and expects that the Supreme Court will review this judgment and that the Parliament will also step in to repeal this archaic law.[36]

Brinda Karat of the Communist Party said the SC order was retrograde and that criminalising alternative sexuality is wrong.[41]

Shivanand Tiwari, leader of Janata Dal United, did not support the Supreme Court decision, calling homosexuality practical and constitutional. He added that 'This happens in society and if people believe it is natural for them, why is the Supreme Court trying to stop them?'[32]

Derek O'Brien of the Trinamool Congress said that he is disappointed at a personal level and this is not expected in the liberal world we live in today.[32]

Legislative action[edit]

On 18 December 2015, Lok Sabha member Shashi Tharoor of the Indian National Congress, whose leaders Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi had earlier expressed support for LGBT Rights,[42] introduced a private member's bill to replace Section 377 in the Indian Penal Code and decriminalize consensual same-sex relations. The bill was defeated in first reading, 71–24.[43] For his part, Tharoor expressed surprise at the bill's rejection at this early stage. He said that he did not have time to rally support and that he will attempt to reintroduce the bill.[43]

In March 2016, Tharoor tried to reintroduce the private member's bill to decriminalize homosexuality, but was voted down for the second time.[44]

Judiciary action[edit]

2009 Naz Foundation V. Govt. of NCT of Delhi[edit]

The movement to repeal Section 377 was initiated by AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan in 1991. Their historic publication Less than Gay: A Citizen's Report, spelt out the problems with 377 and asked for its repeal. A 1996 article in Economic and Political Weekly by Vimal Balasubrahmanyan titled 'Gay Rights In India' chronicles this early history. As the case prolonged over the years, it was revived in the next decade, led by the Naz Foundation (India) Trust, an activist group, which filed a public interest litigation in the Delhi High Court in 2001, seeking legalisation of homosexual intercourse between consenting adults.[45] The Naz Foundation worked with a legal team from the Lawyers Collective to engage in court.[46] In 2003, the Delhi High Court refused to consider a petition regarding the legality of the law, saying that the petitioners, had no locus standi in the matter. Since nobody had been prosecuted in the recent past under this section it seemed unlikely that the section would be struck down as illegal by the Delhi High Court in the absence of a petitioner with standing. Naz Foundation appealed to the Supreme Court against the decision of the High Court to dismiss the petition on technical grounds. The Supreme Court decided that Naz Foundation had the standing to file a PIL in this case and sent the case back to the Delhi High Court to reconsider it on merit.[47] Subsequently, there was a significant intervention in the case by a Delhi-based coalition of LGBT, women's and human rights activists called 'Voices Against 377', which supported the demand to 'read down' section 377 to exclude adult consensual sex from within its purview.[48]

There was support from others like Sunil Mehra, a notable journalist. He was in a committed relationship with Navtej Singh Johar and drew from his personal experiences while protesting. Ritu Dalmia also demonstrated keen activism. Aman Nath, a writer, historian, and hotelier, also fought for the decriminalisation of Section 377. He had a relationship with Francis Wacziarg for 23 years until Wacziarg passed away.[49] Ayesha Kapur became successful within a decade of working in a nascent e-commerce sector. However, she left her job because she was afraid of people finding out about her sexuality. Over time, she gained the courage to come out and challenge Section 377. [50]

In May 2008, the case came up for hearing in the Delhi High Court, but the Government was undecided on its position, with The Ministry of Home Affairs maintaining a contradictory position to that of The Ministry of Health on the issue of enforcement of Section 377 with respect to homosexuality.[51] On 7 November 2008, the seven-year-old petition finished hearings. The Indian Health Ministry supported this petition, while the Home Ministry opposed such a move.[52] On 12 June 2009, India's new law minister Veerappa Moily agreed that Section 377 might be outdated.[53]

Eventually, in a historic judgement delivered on 2 July 2009, Delhi High Court overturned the 150-year-old section,[54] legalising consensual homosexual activities between adults.[55] The essence of the section goes against the fundamental right of human citizens, stated the high court while striking it down. In a 105-page judgement, a bench of Chief Justice Ajit Prakash Shah and Justice S Muralidhar said that if not amended, section 377 of the IPC would violate Article 14 of the Indian constitution, which states that every citizen has equal opportunity of life and is equal before law.

The two-judge bench went on to hold that:

| “ | If there is one constitutional tenet that can be said to be underlying theme of the Indian Constitution, it is that of 'inclusiveness'. This Court believes that Indian Constitution reflects this value deeply ingrained in Indian society, nurtured over several generations. The inclusiveness that Indian society traditionally displayed, literally in every aspect of life, is manifest in recognising a role in society for everyone. Those perceived by the majority as 'deviants' or 'different' are not on that score excluded or ostracised. Where society can display inclusiveness and understanding, such persons can be assured of a life of dignity and non-discrimination.This was the 'spirit behind the Resolution' of which Nehru spoke so passionately. In our view, Indian Constitutional law does not permit the statutory criminal law to be held captive by the popular misconceptions of who the LGBTs are. It cannot be forgotten that discrimination is antithesis of equality and that it is the recognition of equality which will foster the dignity of every individual.[56] | ” |

The court stated that the judgement would hold until Parliament chose to amend the law. However, the judgement keeps intact the provisions of Section 377 insofar as it applies to non-consensual non-vaginal intercourse and intercourse with minors.[54]

A batch of appeals were filed with the Supreme Court, challenging the Delhi High Court judgment. On 27 March 2012, the Supreme Court reserved verdict on these.[57] After initially opposing the judgement, the Attorney GeneralG. E. Vahanvati decided not to file any appeal against the Delhi High Court's verdict, stating, 'insofar as [Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code] criminalises consensual sexual acts of adults in private [before it was struck down by the High Court] was imposed upon Indian society due to the moral views of the British rulers.'[57]

2013 Suresh Kumar Koushal v. Naz Foundation[edit]

Suresh Kumar Koushal and another v. NAZ Foundation and others is a 2013 case in which a two-judge Supreme Court bench consisting of G. S. Singhvi and S. J. Mukhopadhaya overturned the Delhi High Court case Naz Foundation v. Govt. of NCT of Delhi and reinstated Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code.

The United Nations human rights chief Navi Pillay[12] voiced her disappointment at the re-criminalization of consensual same-sex relationships in India, calling it “a significant step backwards” for the country. In the wake of Indian Supreme Court's ruling that gay sex is illegal, UN chief Ban Ki-moon[13] stressed on the need for equality and opposed any discrimination against lesbians, gays and bisexuals.[14]

Soon after the judgement, Sonia Gandhi, President of the then ruling Congress party, asked Parliament to do away with section 377. Her son and Congress Party vice-President, Rahul Gandhi also wanted section-377 to go and supported gay rights.[15] In July 2014, Minister of State for Home Kiren Rijiju in the BJP led Central government told the Lok Sabha in a written reply that a decision regarding Section 377 of IPC can be taken only after pronouncement of judgement by the Supreme Court.[16] However, on 13 January 2015, BJP spokesperson Shaina NC, appearing on NDTV, stated, 'We [BJP] are for decriminalizing homosexuality. That is the progressive way forward.'[17]

2016 Naz Foundation Curative Petition[edit]

On 2 February 2016, the final hearing of the curative petition submitted by the Naz Foundation and others came for hearing in the Supreme Court. The three-member bench headed by the Chief Justice of India T. S. Thakur said that all the 8 curative petitions submitted will be reviewed afresh by a five-member constitutional bench.[8]

2017 Justice K. S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) and Anr. vs Union Of India and Ors.[edit]

On 24 August 2017, the Supreme Court of India held that the Right to Privacy is a fundamental right protected under Article 21 and Part III of the Indian Constitution. The judgement mentioned Section 377 as a 'discordant note which directly bears upon the evolution of the constitutional jurisprudence on the right to privacy.' In the judgement delivered by the 9-judge bench, Justice Chandrachud (who authored for Justices Khehar, Agarwal, Abdul Nazeer and himself), held that the rationale behind the Suresh Koushal (2013) Judgement is incorrect, and the judges clearly expressed their disagreement with it. Justice Kaul agreed with Justice Chandrachud's view that the right of privacy cannot be denied, even if there is a minuscule fraction of the population which is affected. He further went on to state that the majoritarian concept does not apply to Constitutional rights and the courts are often called upon to take what may be categorized as a non-majoritarian view, in the check and balance of power envisaged under the Constitution of India.[9]

Sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy. Discrimination against an individual on the basis of sexual orientation is deeply offensive to the dignity and self-worth of the individual. Equality demands that the sexual orientation of each individual in society must be protected on an even platform. The right to privacy and the protection of sexual orientation lie at the core of the fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution.[9]

..Their rights are not 'so-called' but are real rights founded on sound constitutional doctrine. They inhere in the right to life. They dwell in privacy and dignity. They constitute the essence of liberty and freedom. Sexual orientation is an essential component of identity. Equal protection demands protection of the identity of every individual without discrimination.[9]

However, as the curative petition (challenging Section 377) is currently sub-judice, the judges authored that they would leave the constitutional validity to be decided in an appropriate proceeding. Many legal experts have suggested that with this judgement, the judges have invalidated the reasoning behind the 2013 Judgement, thus laying the ground-work for Section 377 to be read down and the restoration of the 2009 Judgement of the High Court, thereby decriminalizing homosexual sex.[58][59]

2018 Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India[edit]

In 2018, the five-judge constitutional bench of the Supreme Court consisting of chief justice Dipak Misra and justices Dhananjaya Y. Chandrachud, Ajay Manikrao Khanwilkar, Indu Malhotra, and Rohinton Fali Nariman started hearing the challenge to constitutionality of Section 377. The Union Government did not take a position on the issue and left it to the 'wisdom of the court' to decide on Section 377. The petitioners invoked the right to sexual privacy, dignity, right against discrimination and freedom of expression to argue against the constitutionality of Section 377. After hearing the petitioners' plea for four days, the court reserved its verdict on 17 July 2018. The bench pronounced its verdict on 6 September 2018.[60] Announcing the verdict, the court reversed its own 2013 judgement of restoring Section 377 by stating that using the section of the IPC to victimize homosexuals was unconstitutional, and henceforth, a criminal act.[61][62] In its ruling, the Supreme Court stated that consensual sexual acts between adults cannot be a crime, deeming the prior law 'irrational, arbitrary and incomprehensible.'[63]

The Wire drew parallels between the supreme court's judgement and Privy Council’s 1929 verdict in Edwards vs Canada (AG) that allowed for Women to sit in the Senate of Canada. It compared the petitioners to the Canadian Famous Five.[64]

Documentary[edit]

In 2011, italian film maker Adele Tulli, made 365 Without 377 which followed the landmarking ruling in 2009, and the Indian LGBTQ community in Bombay celebrations.[65] It won the Turin LGBT Film Fest award in 2011.[66]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Rajagopal, Krishnadas (7 September 2018). 'SC decriminalises homosexuality' – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^Pundir, Pallavi. 'I Am What I Am. Take Me as I Am'. Vice News. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^'Delhi high court decriminalizes homosexuality'. www.livemint.com. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^Press, Associated (2 July 2009). 'Indian court decriminalises homosexuality in Delhi'. the Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^Editorial, Reuters. 'Delhi High Court overturns ban on gay sex'. IN. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^Monalisa (11 December 2013). 'Policy'. Livemint. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^Venkatesan, J. (11 December 2013). 'Supreme Court sets aside Delhi HC verdict decriminalising gay sex'. The Hindu. ISSN0971-751X. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ ab'Supreme Court agrees to hear petition on Section 376, refers matter to five-judge bench'. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ abcd'Right to Privacy Judgement'(PDF). Supreme Court of India. 24 August 2017. pp. 121, 123–24. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 August 2017.

- ^Balakrishnan, Pulapre (25 August 2017). 'Endgame for Section 377?'. The Hindu. ISSN0971-751X. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^'Supreme Court rights old judicial wrongs in landmark Right to Privacy verdict, shows State its rightful place'. www.firstpost.com. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^'Right to Privacy Judgment Makes Section 377 Very Hard to Defend, Says Judge Who Read It Down'. The Wire. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^Judgment, par. 156.

- ^'Supreme Court Scraps Section 377; 'Majoritarian Views Cannot Dictate Rights,' Says CJI'. The Wire. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^'Section 377 in The Indian Penal Code'. Indian Kanoon. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^'The Indian Penal Code, 1860'(PDF). Chandigarh District Court. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 January 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^'HC pulls up government for homosexuality doublespeak'. India Today. 26 September 2008.

- ^'Rare unity: Religious leaders come out in support of Section 377'. DNAIndia.com. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^'Section 377 and the law: What courts have said about homosexuality over time'. hindustantimes.com/. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^'Gay sex is immoral and can't be decriminalised, Govt tells HC'. outlookindia.com/. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^Thomas, Shibu (29 September 2016). '14% of those arrested under section 377 last year were minors'. The Times Of India. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^India: Repeal Colonial-Era Sodomy Law, report from Human Rights Watch, 11 January 2006.

- ^'Section 389 in The Indian Penal Code'. IndianKanoon.org. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2009.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^Ramesh, Randeep (18 September 2006). 'India's literary elite call for anti-gay law to be scrapped'. The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^Kounteya Sinha (9 August 2008). 'Legalise homosexuality: Ramadoss'. The Times of India. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^Vikram Doctor (2 July 2008). 'Reverse swing: It may be an open affair for gays, lesbians'. The Economic Times. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^Shibu Thomas (25 July 2008). 'Unnatural-sex law needs relook: Bombay HC'. The Times of India. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^'Ban on gay sex violates international law'. Reuters. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^Rameshan, Radhika (13 December 2011). 'BJP comes out, vows to oppose homosexuality'. The Telegraph.

- ^ abcdeJyoti, Dhrubo (12 December 2013). 'Political Leaders React To Supreme Court Judgement On Sec 377'. Gaylaxy. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^'Homosexuality Is Unethical And Immoral: Samajwadi Party'. News 18. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^'Gay sex is immoral and can't be decriminalised, Govt tells HC'. www.outlookindia.com. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^'Section 377: Homosexuality against Hindutva, cannot celebrate it, says BJP leader Subramanian Swamy India News'. www.timesnownews.com. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ abcHans, Namit (14 February 2017). 'Increasing support for gay rights from BJP leaders. A rainbow in sight?'. Catch News. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^Roy, Sandip (3 February 2016). 'The BJP And Its 377 Problem'. HuffPost. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^'BJP supports decriminalization of homosexuality: Shaina NC'.

- ^'Court should take relook at Section 377 after today's verdict: Chidambaram'. United News of India. 24 August 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^Tiwari, Ravish (19 March 2016). 'Section 377: Unlike RSS, BJP shies away from taking a stand on homosexuality'. The Economic Times. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^'Section 377: Where does each party stand?'. The News Minute. 29 November 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^'Statements of Sonia, Rahul Gandhi and Kapil Sibal on Section 377 exposes character of Congress leaders: Baba Ramdev'. DNAIndia.com. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ ab'Shashi Tharoor's bill to decriminalise homosexuality defeated in Lok Sabha'. IndianExpress.com. 18 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^'BJP thwarting Bill on gays: Tharoor'. The Hindu. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^'Chronology: 8-year-long legal battle for gay rights'. CNN-IBN. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^Kian Ganz (2 July 2009). 'Lawyers Collective overturns anti-gay law'. legallyindia.com. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^Sheela Bhatt (3 February 2006). 'Gay Rights is matter of Public Interest: SC'. Rediff News. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^Shibu Thomas (20 May 2008). 'Delhi HC to take up PIL on LGBT rights'. The Times of India. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^'Section 377: The famous and fearless 5 who convinced SC - Times of India ►'. The Times of India. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^'Gay in India, Where Progress Has Come Only With Risk'. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^'Centre divided on punishment of homosexuality'. DNA.

- ^'Delhi high court all set to rule on same-sex activity petition - Livemint'. www.Livemint.com. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^'Moily signals rethink on anti-gay law'. The Times of hindustan. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ ab'Delhi High Court legalises consensual gay sex'. CNN-IBN. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^'Gay sex decriminalised in India'. BBC. 2 July 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^'Naz Foundation v. NCT of Delhi'(PDF). Delhi High Court. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^ ab'Verdict reserved on appeals in gay sex case'. The Hindu. New Delhi, India. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^'Legal experts on 377 and Right to Privacy'. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^'The Hindu on 377 and Right to Privacy'.

- ^'Section 377 Verdict By Supreme Court Tomorrow: 10-Point Guide'. NDTV.com. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^'One India, Equal In Love: Supreme Court Ends Section 377'. NDTV.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^'India decriminalises gay sex in landmark verdict'. www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^''Gay sex is not a crime,' says Supreme Court in historic judgment'. The Times of India. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^'From Canada to India, 'Valiant Five' Have Secured a Marginalised Group's Rights'. The Wire. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^'365 without 377 - Adele Tulli'. www.queerdocumentaries.com. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^Paternò, Cristiana (11 February 2019). 'Adele Tulli: 'Italy is a lab for gender''. news.cinecitta.com. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

External links[edit]

- Male-to-male sex, and sexuality minorities in South Asia: an analysis of the politico-legal framework, Arvind Narrain & Brototi Dutta, 2006.

- Section 377 – Indian Penal Code, 1860 (Mobile)